Little Boy & Fat Man — The Atomic Bombs and Their (Pop-) Cultural Implications

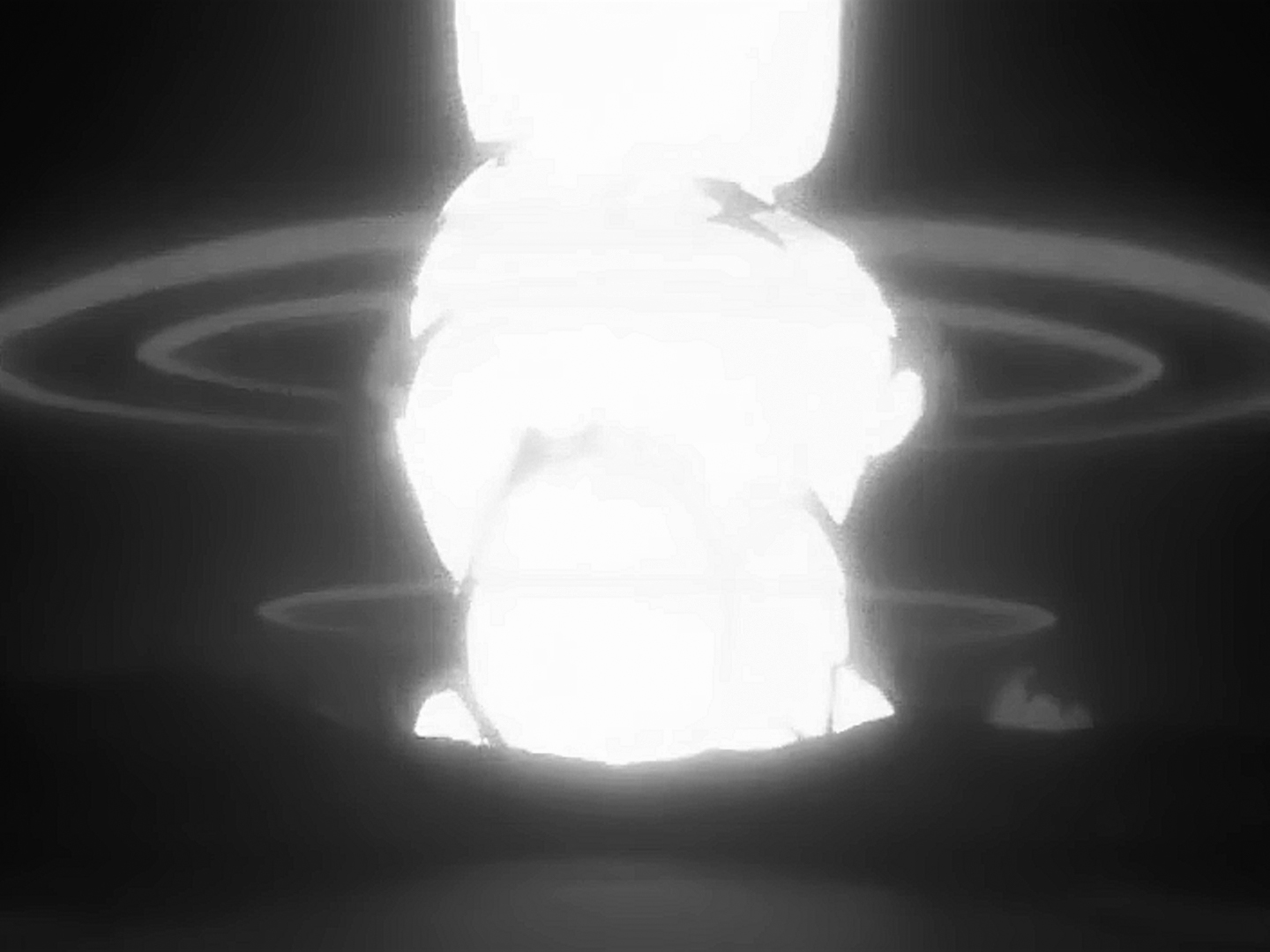

During the final stages of World War II, the United States detonated two nuclear weapons over the Japanese cities of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. It was essential for both — the American and Japanese post-war societies — to address the atomic bombs. Naturally, the events were collectively remembered in an opposing manner by the victor and the vanquished.

Little Boy and Fat Man — as called by the Americans — remain the only examples of nuclear weapons used in warfare and became the symbol of the Japanese defeat. The post-war society was shaped in the shadow of the mushroom clouds of the atomic bombs and the traumatic events became a touchstone for the development of the national identity. These values were ultimately constituted by the atomic trauma and expressed in a vast number of cultural works, including the Japanese animated movies. It is worthwhile to explore the historical events and their influence to set a frame for an interpretation of any medium, dealing with the atomic bombings.

The use of the atomic bombs against two densely populated Japanese cities were fitted neatly into American’s triumphal Good War narrative. In this context, the bombs were necessary to persuade Japan’s military leaders to surrender, and therefore to save countless thousands of American lives. It is a simple narration omitting the simultaneous declaration of war by the Soviet Union, solidifying the absoluteness and unconditionality of the surrender.

This narrative however, determined the American post-war identity and the euphoric attitude towards the fast scientific advances impersonated by the success of the nuclear bombs. Exemplary, this positive connotation of nuclear power permeated the American pop-culture and lead to the emergence of heroes equipped with world-saving superhuman abilities after they were exposed to particle radiation.

The emergence of Japan’s collective conciousness of the atomic bombs took quite some time. U.S. occupation authorities censored writings, photographs, and pictorial depictions of Hiroshima and Nagasaki for many years, out of fear these would provoke anti-American hostility. Therefore, the Japanese as a whole did not begin to visualize the human consequences of the bombs in concrete, vivid ways until three or four years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been destroyed. The first graphic depictions of victims seen in occupied Japan were not photographs but drawings and paintings by the wife-and-husband artists Maruki Toshi and Maruki Iri.

The first compilation of photographs from the two ground zeros was not published in Japan until the occupation ended in August 1952, and the first famous Japanese photographers did not visit the two cities to photograph scarred survivors until 1960. In the print media, the easing of censorship in late 1948 finally paved the way for publication of reminiscences, poems, essays, and fictional re-creations by hibakusha (surviving victims of the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki).

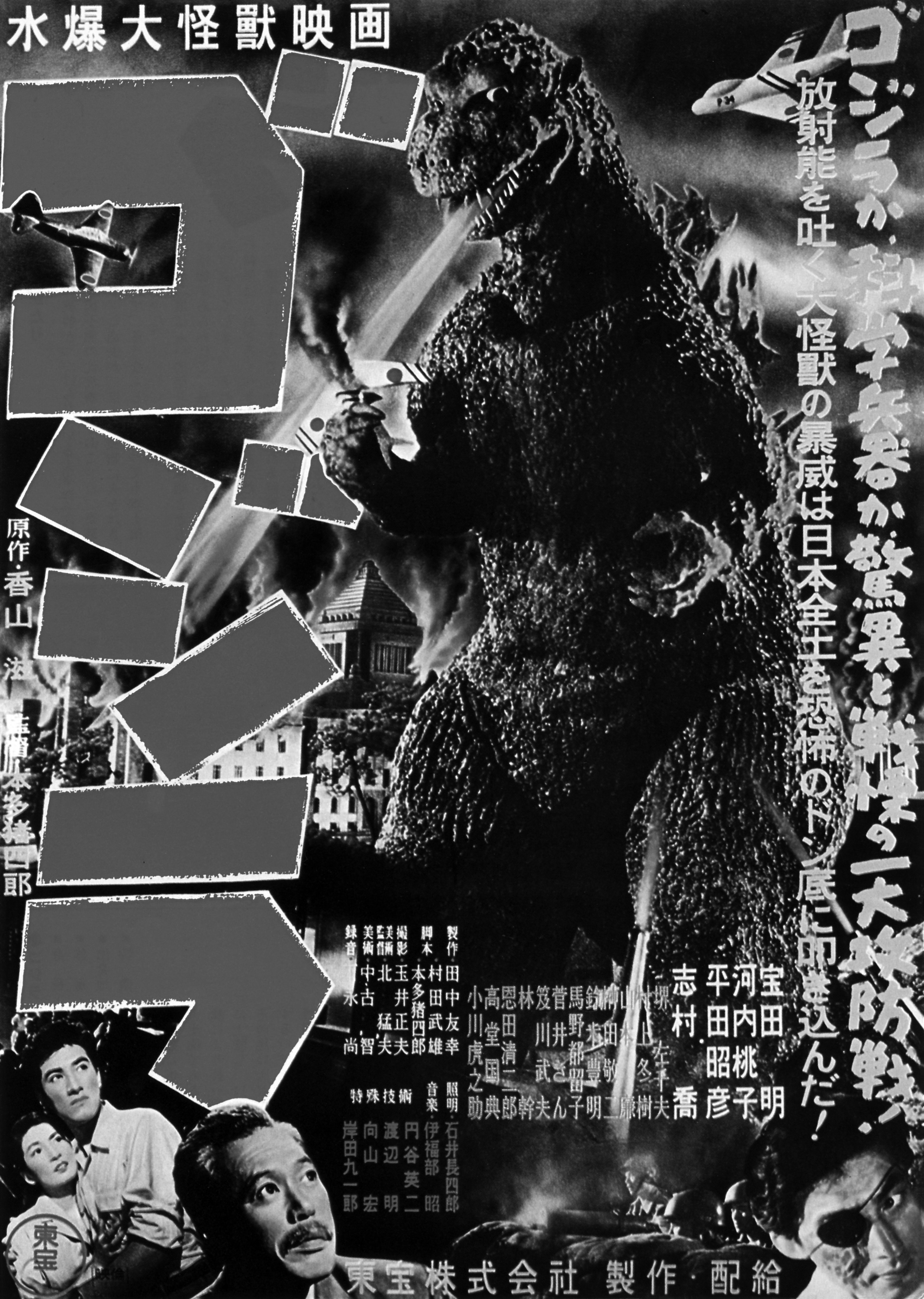

By the early 1950s, fear of a nuclear “World War III” had become almost palpable in Japan. When fallout from an U.S. thermonuclear test on the Bikini atoll irradiated the crew of a Japanese fishing boat, the public was primed to respond with intense emotion. This same turbulent period also saw the birth of “Godzilla” in November 1954, Japan’s enduring contribution to the cinematic world of mutant science-fiction monsters spawned by a nuclear explosion. It still represents the harbinger of man-made apocalypse, reviving the atomic trauma and burning cities, emphasizing the need of Japanese society to overcome catastrophic events as a united entity.

The director Kurosawa Akira released the film entitled “I Live in Fear” in 1955, in which fear of atomic extinction drives an elderly man insane.

In the early 1970s, Nakazawa Keiji, a cartoonist for children’s publications who had been a seven-year-old in Hiroshima when the bomb was dropped, achieved improbable success with a graphic serial built on his family’s own experiences as victims and survivors. Nakazawa’s “Barefoot Gen” was serialized in a boy’s magazine with a circulation of over 2 million and ran to some one thousand pages before the series was terminated—surviving thereafter as both an animated film and a multivolume collection.

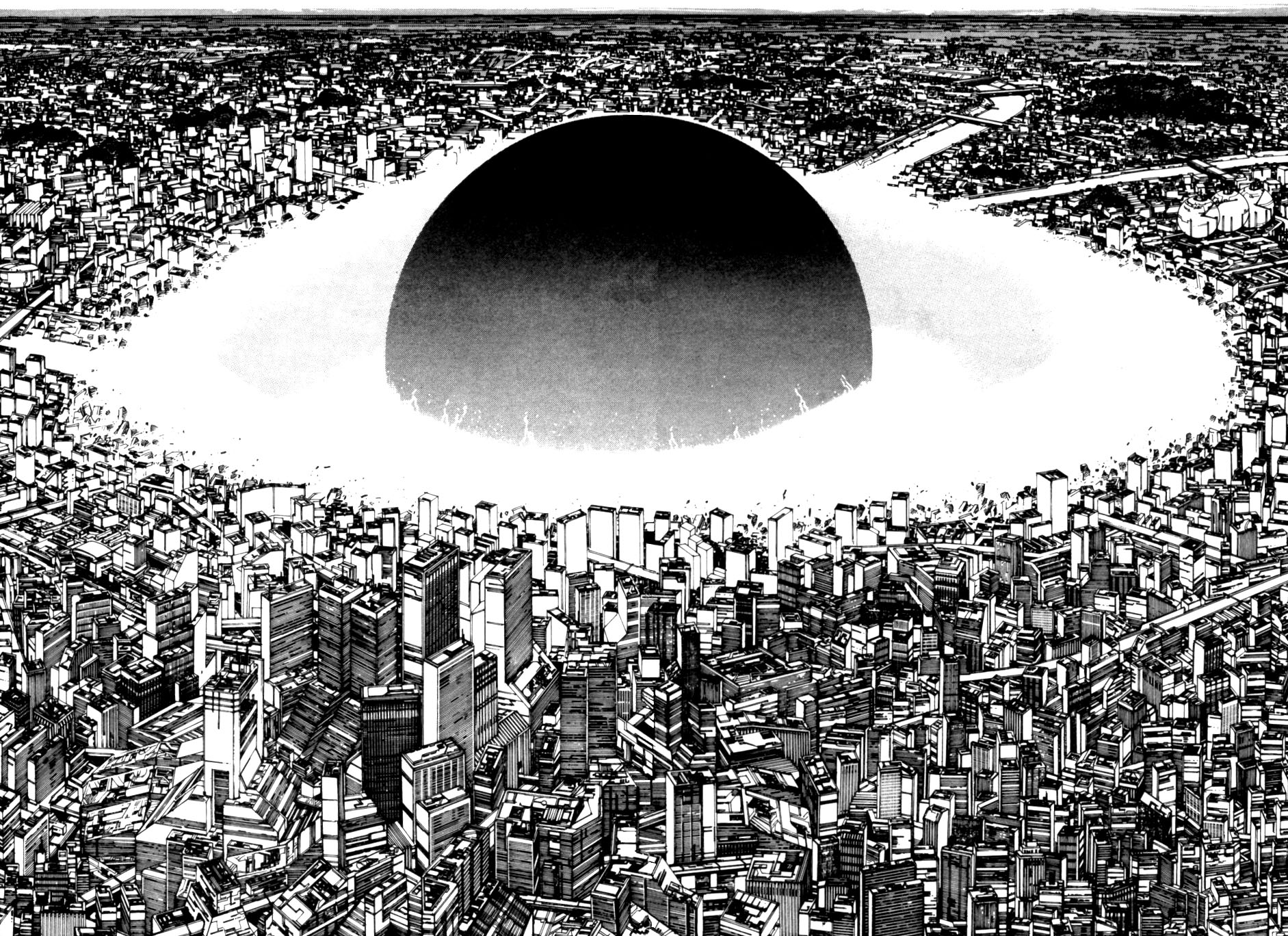

Other popular appreciation of the bombs in anime are set in a future dystopian Japan. As one of the most popular anime ever, “AKIRA” — based on manga of the same name — is a cyberpunk animated film released in the 1980s that is noted for its bleak depiction of a futuristic yet decaying Japan. The opening scene shows the destruction of Tokyo in 1988 by an explosion reminiscent of a nuclear bomb. It also tackles the fear of mutation and deformation often depicted in pop-culture and attributable to the consequences of radiation which were only slowly discovered.

“Neon Genesis Evangelion”, a short but popular and widely influential science fiction anime from 1995, serves as a striking example of nuclear undertones in Japanese popular art and caused a controversy due to the depiction of a nuclear explosion in its very first episode as well as ultraviolent scenes in the later course.

Hayao Mizayaki, the main figure behind Studio Ghibli is mostly known to have an ambivalent relationship towards technological progress, rather known for his empathetic nice depictions of nature. He frequently addressed the human ability for self-destruction and in “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind” probably his most direct reference to the atomic bombs can be observed.

The anime “Grave of the Fireflies” from 1988, produced by the popular studio Ghibli, struck the same realistic tone as Barefoot Gen and tells the story of two siblings in the city of Kobe during World War II. The constant threat of bombers lingers throughout the film, showing the endless firebombing of Japanese cities and towns during the war.

The Japanese used certain images to process their imperialistic past and the nuclear bombs in particular. Takashi Murakami addressed those in a critical manner. He is a major proponent of the notion that Japan’s obsession with anime, manga, excessive violence, and even cuteness derives from denial of the emotions brought about by the atomic bombings and Japan’s aggression during the Second World War.

The Anime “In this Corner of the World” was directed by Sunao Katabuchi, based on the book of Fumiyo Kōno. It retells the events during World War II from the limited point of view of a young Japanese woman and draws a lot of its inspiration from real war documents and photographs. The protagonist Suzu moves to the city of Kure, close to Hiroshima, acting as Japan’s single largest naval base and arsenal which was heavily effected by the air raids during the last phase of the war and witnessed the use of atomic bomb.

Historical Background

To comprehend the national trauma caused by the fall of the Japanese empire it is important to understand the imperative will to emulate their imperialistic paragons and extend the emperor's influence over the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. At the peak of imperial expansion, poets, priests, and propagandists alike extolled the superi-ority of the “Yamato race” and the sublime destiny of the Imperial Way. This aspired Co-Prosperity Sphere was but a chimera; the euphoria of the first half-year of the Pacific War but a dream within a dream. Long after it had become obvious that Japan was doomed, its leaders all the way up to the emperor remained unable to contemplate surrender. They were psychologically blocked, capable only of stumbling forward. From the massacre of Nanking in the opening months of the war against China to the massacre of Manila in the final stages of the Pacific War, the emperor’s soldiers and sailors left a trail of unspeakable cruelty and rapacity. The population at home watched helplessly as fire bombs destroyed their cities-all the while listening to their leaders natter on about how it might be necessary for the “hundred million” all to die “like shattered jewels”, rather than surrender to the enemy. The most obvious legacy of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was death and destruction. In China alone, perhaps 15 million people died. The Japanese lost nearly 3 million people and their entire empire as well.

Because the defeat was so shattering, the surrender so unconditional, the disgrace of the militarists so complete, starting over involved not merely reconstructing buildings but also rethinking what it meant to speak of a good life and good society. However, the preoccupation with their own misery that led most Japanese to ignore the suffering they had inflicted on others illuminates the ways in which victim consciousness colors the identities that all groups and peoples construct for themselves. Historical amnesia concerning war crimes has naturally taken particular forms in Japan, but the patterns of remembering and forgetting are most meaningful when seen in the broader context of public memory and myth-making generally. It is therefore of importance to reflect on the historical narrative used in animated movies contributing to the general remembrance and the balance between victimization of the imperialistic japan or realistic representation of the horror of war.

RESEARCH AND TEXT BY: Christoph Noller, 2018

SOURCES: Dower, J. W. (2000). Embracing defeat: Japan in the wake of World War II. WW Norton & Company. Dower, J. W. (2014). Ways of forgetting, ways of remembering: Japan in the modern world. New Press, The.